Part 3: What Does "Program Closure" Mean for Frontline Programs?

"Finding Your Finish Line" Series

Zosia’s Challenge: Our fictional protagonist today is Zosia ( “ZAW-shah”, rhymes with “Sasha”), a program management professional (PgMP*) at a large non-profit organization. Zosia has led a program for the past four years, helping older adults learn to use new technologies to support their healthcare journeys (such as telemedicine, remote monitoring, wellness apps, and the like).

The initial years of the program were admittedly pretty hectic. Her program was hastily launched in response to the COVID-19 pandemic with little to work from. Through trial and error, her team slowly built an impressive set of offerings, including educational courses, a popular newsletter, and a financial assistance fund. Most of the work now has a regular schedule, and Zosia is assured of ongoing funding for the foreseeable future.

In contrast to those early years, Zosia shows up at work every day knowing, for the most part, what needs to happen. Certainly, with the expansion of artificial intelligence (AI), there’s tremendous change afoot in the technologies her program promotes, but the underlying structure was designed to adapt to these shifts. Zosia has finally reached a moment where things feel really good at work.

Then she’s studying “The Standard for Program Management,” by the Project Management Institute (PMI), and reads about the program closure phase (1, p.148). Apparently, programs are supposed to close, and this throws her. She’s worked so hard, and the last thing she can imagine is intentionally shutting down her program or transitioning it to another part of the organization. It wouldn’t make any sense.

This leaves Zosia wondering: does any of PMI’s guidance on this stage of a program’s lifecycle actually apply to her, or is it an area of the manual she should just ignore?

Let me make the case that Zosia should run a “program closure” process, but not to shut her work down. Instead, to fully prepare her program and career for long-term sustainability.

About the “Finding Your Finish Line” series

This past summer, I wrote the “The Great Uncertainty” series, five articles focused on navigating the prospect of program cancellation for program management professionals (PgMPs) affected by the federal funding cuts.

This series is meant to explore the other half of that closure coin— why and how do we intentionally manage our programs toward a favorable ending? In studying the PMI’s Standard for Program Management (SPM), I found a significant difference between PMI’s guidance on program closure and my field experience, suggesting that “positive program closure” remains somewhat of a mystery for non-profits. This article, Part 3, dives into how the program closure process applies to frontline programs – i.e., programs that are typically not intended to close.

Why do frontline programs not mix well with closure?

In Part 2 of the “Finding your Finish Line” series, we examined the underlying anatomy of a strong program close. Aligned with PMI’s guidance, this is a process in which a program that has worked on an underlying operational improvement (i.e., backline program) transitions its work to operations (HR, IT, etc.) for ongoing management and sustainment.

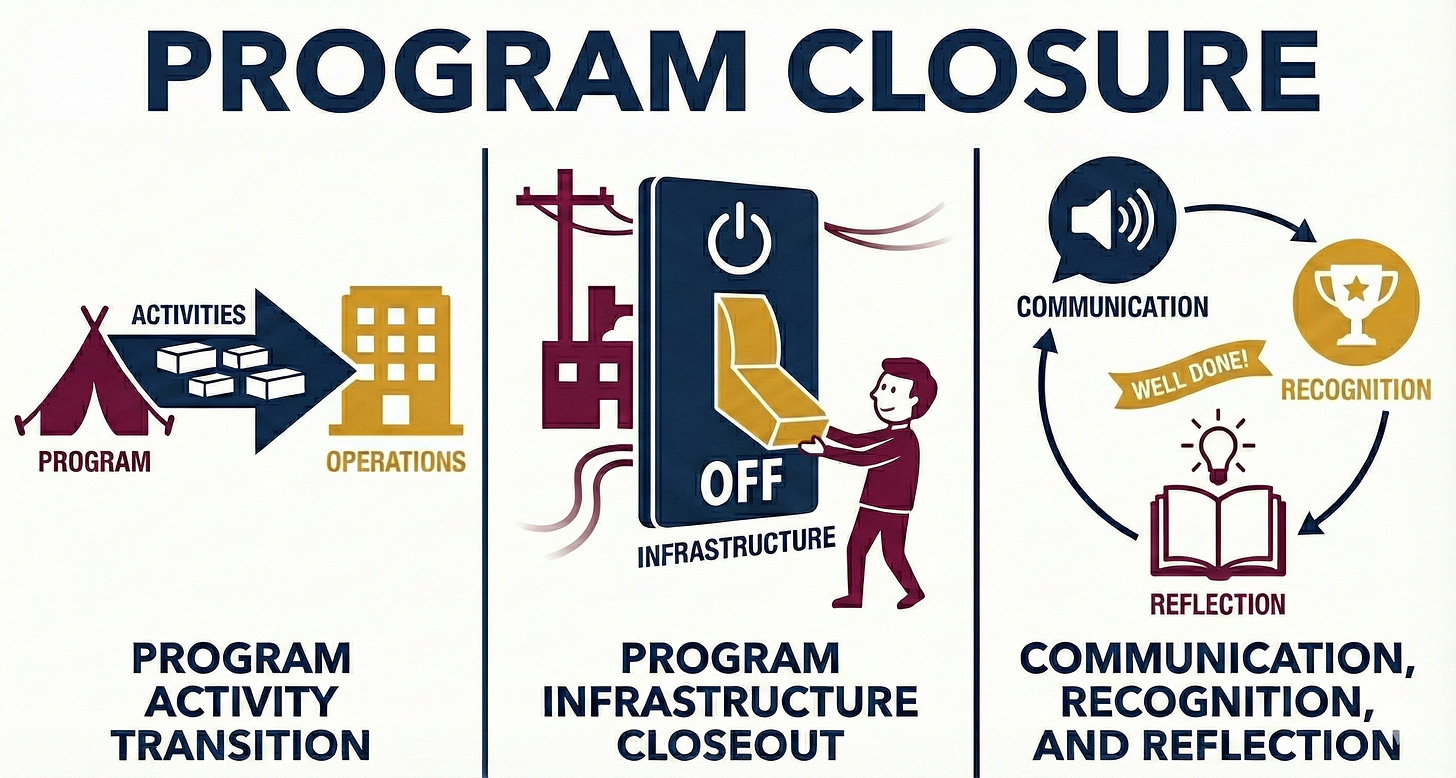

In these scenarios, the PgMP is formally tasked with completing program closure activities, which I grouped into three major buckets: 1) program activity transition, 2) program infrastructure closeout, and 3) communication, recognition, and reflection.

But what if, like Zosia, you are not running that kind of program? Many non-profit organizations host “programs” that provide goods and services directly to customers and generate their own revenue. I call these “frontline programs,” and they are really not built to end – at least not until the underlying social goal is achieved (cancer cured, digital literacy gap erased, etc.) or they hit an insurmountable roadblock, usually budget cuts. Thus, on the face of it, frontline programs and positive program closure are like oil and water; they don’t mix well.

But I want to recommend that for the keen PgMP running a frontline program, there is a way to apply the underpinnings of positive program closure, and that doing so benefits the success and growth of your program as well as your career.

Recognizing your program’s inflection point

Similar to the way positive program closure for backline programs is a transition to operations, we can think of program closure for frontline programs as the switch in the program’s lifecycle between development and production. Based on my professional experience, this moment admittedly occurs quite gradually and over a long period of time. Consequently, it’s an easy moment to both miss and even confidently judge when it occurs.

Some signals that your program is largely out of the exploratory phase and into routine production are:

You can write a standard operating procedure (SOP) about how to run most of your program’s products and services.

You can schedule out the program’s activities well in advance (6 months or more).

You’ve hosted the event, course, or activity (i.e., the projects) multiple times. The core of the work is starting to repeat.

If needed, you could hand off the program to a new PgMP and be fairly confident the program wouldn’t lose significant momentum.

This shift occurs through an accumulation of regularity. You are trying new ways to approach your mission, evaluating what works, trying again, and, over time, you start to develop a repeatable, standardized approach. Yes, there will always be work to do, with new demands coming down the pipeline, but the majority of the program’s work is routine. Similar to the example of Zosia’s program above.

It’s at this point that running the three sets of activities in the “program closure” process can be beneficial to long-term success – both for your program and your career.

Applying program closure to your frontline program

As Zosia stands at that inflection point in her program, how would she apply the “program closure” process? All three of the buckets of work described above apply, but they shift their focus slightly.

“Program Activity Transition” becomes “Program Playbook Creation.”

“Program Infrastructure Closeout” becomes “Program Role Alignment.”

“Communication, Recognition, and Reflection” remains unchanged

A. Program Playbook Creation

When a backline program hands off responsibility to operations (i.e., a program activity transition), there’s an inherent push to document and clean up the data to properly train new staff on your work. For Zosia, her program team has organically become “operations” over time, having learned the work along the way. While it’s tempting to let business run as usual, strong program leadership means putting the team through a formal documentation process and creating a “program playbook.”

Further, it’s a time to clean out that digital closet and organize the program’s folder to streamline materials relevant to the program’s current operations, archiving the outdated materials, prototypes, and irrelevant past projects – do not let them stack up. Through this process, Zosia is reducing the risk of relying too heavily on individualized knowledge and creating new efficiencies by clarifying activities and responsibilities.

B. Program Role Alignment

For a backline program, “Program Infrastructure Closeout” is the set of activities needed to disband the program team so that they can be reassigned to the next big operational improvement program. For a frontline program, Zosia’s not looking to redeploy her team, but she should take a moment to consider how the program’s evolution into this production phase intersects with everyone’s career trajectories. As the program’s activities have standardized, the requisite skill sets for the jobs have changed – roles are now less about exploration and more about refined execution and, potentially, the ability to scale operations.

For Zosia, she may have tremendously enjoyed the challenges of figuring out a brand-new program and thrived amongst the uncertainty. The prospect of knowing what she’ll be working on every day and focusing on more routine management tasks may be quite boring to her. A signal that she is better off transitioning the program to a new leader (maybe to a high-performing project manager) and moving on to create the next new program. Or, in contrast, she may be enjoying the outcomes of her hard work and the benefits of having developed a unique expertise in digital literacy. Zosia may be looking forward to exploring how AI will change the landscape of elder care and refining her program to meet these new demands. In this case, staying as the lead of the program makes sense.

There’s no right answer to what’s next for Zosia, but it’s worth contemplating how the phase change of leading a program in development versus production will influence her long-term career.

The same applies to your program team’s career trajectories, and as a PgMP, you play a big role in how that unfolds. If Zosia’s now-standardized program is expected to scale, she’ll likely be able to offer her staff continued professional advancement and new operational challenges. If the plan is to sustain the program at its current level, it’s likely that the staff who thrived in the development phase will be overqualified for the routinized work and also have limited opportunity for promotion. Those conversations are best had sooner rather than later, so Zosia can appropriately set the expectations for her team members and support them if a transition to a new opportunity – hopefully within the same organization – is needed.

C. Communication, Recognition, and Reflection

Finally, there’s a need to recognize the “win” of developing a successful program from scratch. For frontline programs, it’s easy to highlight project wins or note positive key performance indicators (KPIs) in presentations. But since the transition between development and production has no definitive date, you have to name the moment yourself. By hosting a “program closure” process, you can celebrate, reflect, and also communicate your accomplishments to everyone. For Zosia, it gives her an opportunity to present her “program playbook” to her leadership. It prompts a time for a debrief, not at the project level, but at the holistic program level – to uncover lessons learned on an enormous and potentially quite novel amount of work. Finally, it’s a good time for Zosia to update her resume and LinkedIn profile, documenting in as quantitative of terms as possible the outcomes and benefits of her work.

The benefits of the program closure process

Program closure for a frontline program is about intentionally processing your program’s transition from development to production – a time that can easily pass you by if you’re not looking out for it. Key benefits of running the process include:

Standardizing your program operations to improve efficiencies and ensuring new staff can take over if needed.

Aligning the reality of your program’s trajectory with the team’s individual career goals.

Learning from the big picture of building a program and having the right framing to communicate your accomplishments to your community.

Another benefit of recognizing “program closure” in a frontline program’s lifecycle happens far earlier. It gives you definable terms for use during the program’s definition phase: when you’re writing the program’s business case and program management plan. At the start of a novel program, you know the problem you are trying to solve, but likely only have your suspicions on how to fix it. Defining “program closure” as the shift from development to production provides an achievable endpoint for the work (as opposed to “until you solve the social issue completely”), creating more reasonable boundaries for the work and not pigeonholing yourself into a program that will never be complete.

That leads us to the final problem: the words used to define this phase, “program closure,” really aren’t a good fit for frontline programs. Using it in a work setting would reasonably be mistaken as a request to shut down the program. Someday – not today – I’m going to come up with a better term. For now, I’m not willing to deviate from the defined vernacular, but know it’s on my mind.

“Pluribus Theme Song”

I’ll leave you with the simple idea that if program closure is good enough for backline programs, I can’t see why it wouldn’t be a worthwhile set of activities for frontline programs. Doing the deeper work to understand that your program has entered a new phase in its lifecycle can have many benefits, both for the work itself and for the program team’s career management. I do believe we should build “program closure” into the lifecycle for frontline programs, but we also need to tweak the focus of the work and give the phase a new name (let me know if you have any suggestions in the comments section below).

This article’s song pairing is “Pluribus Theme Song” by Dave Porter. I finished the first season of the television show “Pluribus” on Apple TV and have moved on to binge-listening the “Official Podcast.” If you are a details person, the show and podcast are completely fascinating. Regarding this song, we typically only hear the first part during the show’s opener, but try listening to the entire score. The middle of the song sounds like curiosity and uncertainty instrumentalized. Similar to how a program can feel in its early stages of development, where, like the show, you don’t know how it’s going to end. Enjoy.

References

Project Management Institute PMI. The Standard for Program Management - Fifth Edition. Project Management Institute; 2024.

*In “The Non-Profit Program,” I use the term program management professional with the acronym PgMP to refer to anyone working or interested in program management, regardless of their official job title or credentials. This usage differs from the typical professional usage, in which PgMP indicates the successful completion of the Program Management Professional (PgMP) certification offered by the Project Management Institute (PMI).