Part 2: The Anatomy of a Strong Program Close

"Finding Your Finish Line" Series

In my last article, I promised an explanation on the benefits of steering programs towards closure - a behavior that, for many non-profit programs, is antithetical to the work. But when I sat down to write about benefits, a different question pressed itself into the forefront: What does working on a positive program closure mean?

Before we can understand the benefits of program closure, we need to walk through the inner workings of a strong program close.

About the “Finding Your Finish Line” series

This past summer, I wrote the “The Great Uncertainty” series, five articles focused on navigating the prospect of program cancellation for program management professionals (PgMPs*) affected by the federal funding cuts.

This series is meant to explore the other half of that closure coin— why and how do we intentionally manage our programs toward a favorable ending? In studying the Project Management Institute’s (PMI’s) Standard for Program Management (SPM), I found a significant difference between PMI’s guidance on program closure and my field experience, suggesting that positive program closure remains somewhat of a mystery for non-profits. This article, Part 2, dives into the activities surrounding a strong program closeout, specifically for backline programs.

Positive vs. negative program closure

Positive program closure happens when you have fulfilled your intended program management plan (i.e., completed all your projects) and started to realize the intended benefits of the work. At this point, the ideal is to “close your program” – which admittedly doesn’t really mean close, more a transfer… a shift… a change, if you were, but not the dreaded end. These are the activities necessary to embed your program’s outputs into everyday operations and ensure the appropriate managing parties (IT, HR, Operations, etc.) are set to keep the work going.

Another rare form of positive program closure happens when the program’s overarching goal is truly met. In this case, a program’s activities are formally retired. Still, at non-profits, where programs typically focus on broad social missions, this type of achievement is difficult to pin down. Still, occasionally we do conquer entire issues. For example, if you were running a smallpox prevention program in 1980 when the World Health Organization declared the disease eradicated, you could legitimately hang up your hat with great content. Again, total solutions to social problems are unique circumstances, so while I’ll acknowledge that it can happen, it won’t be the focus of this discussion moving forward.

Conversely, negative program closure is any scenario in which your program completely shuts down its work while the problem you’re trying to solve remains outstanding. For example, all the programs shut down due to budget shortfalls caused by the shifts in federal funding are instances of negative program closures. These scenarios represent someone’s professional heartbreak, often a PgMP. If you need guidance on navigating a negative program closure, please see my series “The Great Uncertainty: Preparing for your Program’s Cancellation.” It covers a broad range of topics from program advocacy through preservation to starting the job search.

The three buckets of program closure activities

So what happens when you have completed your projects and are seeing the aggregate benefits of all the work? Your program enters the next phase in its life cycle, called program closure, which PMI defines as “program activities necessary to retire or transition program benefits to a sustaining organization and formally close the program in a controlled manner” (1 p.233).

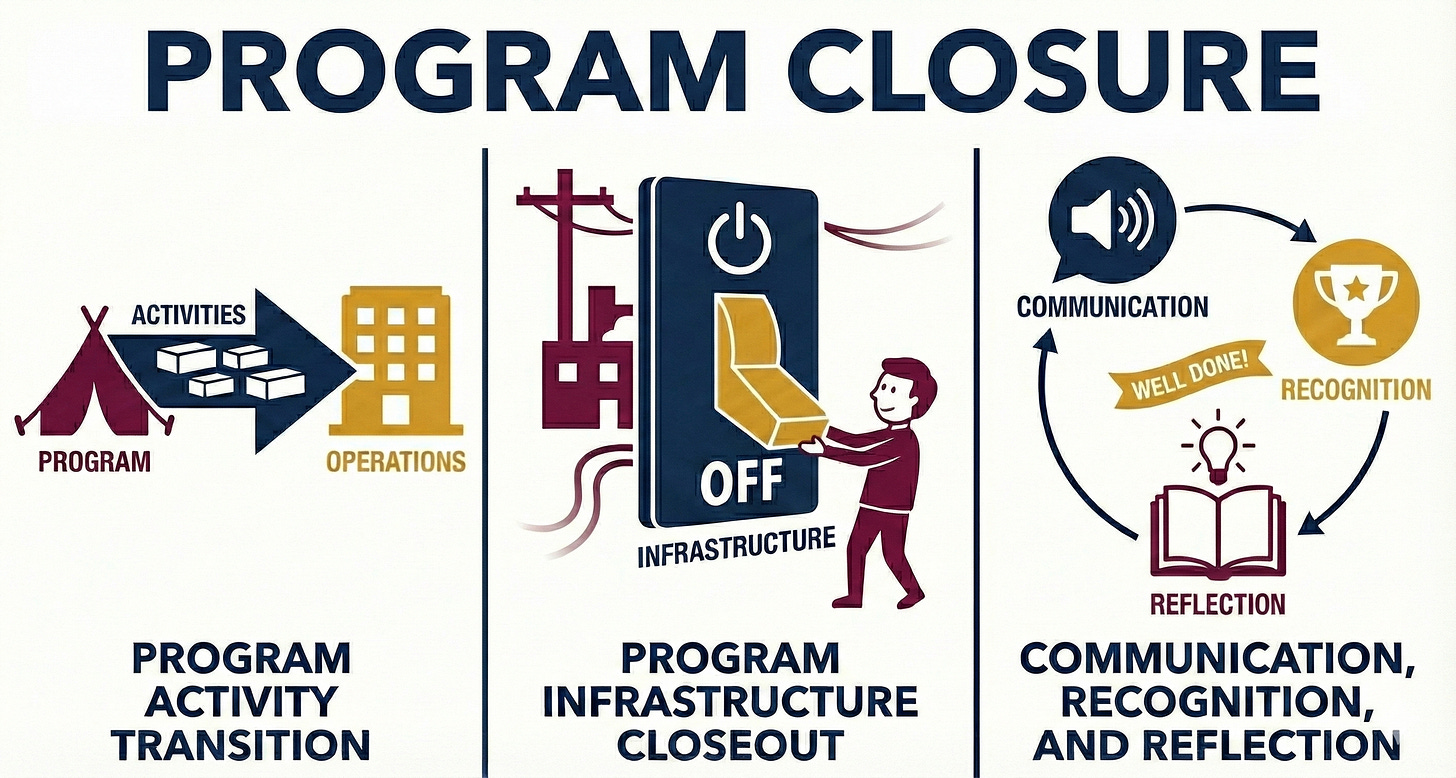

Your goal during a positive program closure is not to stop the program’s actual activities, but to officially embed them into daily operations while removing the higher-cost program infrastructure that was needed to support the initial build. These closeout activities can be categorized into three major buckets:

Program Activity Transition: All services, operations, databases, etc., that you installed at the company must be fully transitioned to another person or group for ongoing management. You’re looking at all the program outputs, such as operations, products, data, performance metrics, and even known risks, to ensure the program’s activities remain online and sustain their intended benefits.

Program Infrastructure Closeout: Creating change requires intensive labor, dedicated expertise, and often significant time. This lift is why programs as a unit of work exist. But once your work is part of everyone’s standard day, such a dedicated allocation of resources is no longer needed. As part of the closeout process, you need to shut down your program’s infrastructure. This work includes letting your staff move on to their next projects, closing out contracts, and ensuring all payments are made.

Communication, Recognition, and Reflection: This is the softer side of closure, where you address its emotional and interpersonal aspects. Despite success, closure often means a break in daily professional relationships and the discomforting prospect of change. There’s grief to recognize in that process. You want to close down your program in a way that ensures your community feels supported in their own transitions and acknowledged for a job well done. Along with finding ways to celebrate, it’s also an opportunity for reflection, team downtime to assess what went well and what didn’t, and maybe a presentation to share these lessons learned. Be sure to document these findings for future teams as well. Finally, there’s your own career management to consider. Make sure to cement ties with the people you worked with - update that holiday card list - and document the numerical impact of your work on your resume while the info is fresh. I also highly recommend posting a few times on LinkedIn, which publicly timestamps your work and makes it easier for future employers to verify your past accomplishments.

For all the reasons I noted in the first article in this series, I suspect that for many non-profit PgMPs, the idea of program closure remains strange. These buckets of work hopefully seem logical, but what does positive program closure actually look and feel like? I’ll go back to early in my career, when I participated in a highly structured, very prescriptive program that had a well-defined end embedded right at the start. Reflecting now, it’s quite likely the cleanest program closure I’ll ever attend.

Field Experience: A very structured program’s ending

Over a decade ago, I worked as a consultant at a mid-sized firm, serving at the project management level on a year-long program to help the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic (YVFWC) become Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) certified. YVFWC is a network of community health centers in Washington and Oregon that were working to improve their healthcare services and financial sustainability.

Assuming most readers are not familiar with PCMH, it is a highly structured program of activities and infrastructure upgrades. A governing organization, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), administers the standards and grants accreditation to those who qualify. Gaining PCMH recognition indicates that you are a top-notch healthcare system and can generate higher reimbursement rates from insurance companies (i.e., you get paid more).

I worked as a PCMH coach and helped three YVFWC community health centers in Oregon adopt these standards. Some of this work involved changing operations, such as ensuring each clinic offered office visits outside of the standard 9-5 business hours. Others were cultural, such as teaching aspects of a team-based care model. Some changes were more technical, focused on adopting stricter practices in electronic medical record documentation. While the larger program dictated the methods, I applied them in smaller project chunks across my three clinics; teaching, monitoring, and tracking as we went. Throughout, the work was slowly embedded into the standing operations of each clinic, and after a whole year, we submitted what felt like a mountain of paperwork to NCQA. In 2014, YVFWC received NCQA Level III PCMH recognition.

The projects were completed and benefits delivered; it was time to enter the program closure stage. The PCMH program was formally closed out following the same buckets of activities described above:

Program Activity Transition: The program had successfully implemented new processes, methods, data analytics, and cultural expectations into the workplace. I didn’t have direct insight into the data analytics support, so I’m unclear on that part of the handoff. My clinic coaching responsibilities officially shifted to the office managers and the medical director for the clinics.

Program Infrastructure Closeout: I, as a project management level resource, was subsequently released to pursue other client work for the consultancy.

Communication, Recognition, and Reflection: I vividly remember having many nice goodbyes with the teams at my clinics, who were immensely kind. I also recall the bigger party at the organization’s headquarters, a good buffet, and hearing from YVFWC’s Executive Director, who championed this vision. I can’t recall if the entire program team ever sat down for a lessons-learned debrief. However, the medical director of my three clinics was visiting Boston shortly afterwards, and we co-presented on the clinics’ PCMH experience to my entire consultant company. I was told it was the first time a clinical partner had presented at the company’s headquarters and publicly shared their experiences working with our consultancy. 😊

A nuts-to-bolts PCMH installation is an extensive program with the close built right in. This case shows that a closure is integral to a program’s process and must be done well, particularly to sustain the intended benefits. While I can’t speak directly to YVFWC’s experiences maintaining PCMH in the succeeding years, as of today, YVFWC remains an independent organization (not easy in an era of consolidation), still holds PCMH accreditation, and appears to have significantly expanded its practice network—all good signs of a healthy organization.

“That Christmas Morning Feelin”

PMI does a great job detailing the desired endpoint for programs and the work underlying a successful transition and closeout of program operations. I’ve found it helpful to group these activities into three major buckets and added in a few components of my own - particularly around acknowledgment and communication.

But here’s the catch. This model of program closure is primarily designed for backline programs, where you work to improve the underlying operations of an organization. In such a case, transitioning the ownership of activities and removing yourself from the mix is possible. But what if you are developing a frontline program that directly serves customers and generates self-sustaining revenue? Does anything around this world of “positive program closure” still apply?

More on this line of inquiry in the next article of the “Finding Your Finish Line” series… and then the article on the benefits of positive program closure, I promise!

To not leave you without a song pairing for Christmas, here’s one of my favorite new holiday songs, “That Christmas Morning Feelin’” from the movie “Spirited.” Enjoy and have a wonderful winter break.

P.S. I also learned my lesson on trying to write while celebrating a major holiday. I’ll be on break for Christmas with the next installment of “The Non-Profit Program” coming out on Wednesday, January 7th, 2026.

P.P.S Happy New Year too!

References

Project Management Institute PMI. The Standard for Program Management - Fifth Edition. Project Management Institute; 2024.

*In “The Non-Profit Program,” I use the term program management professional with the acronym PgMP to refer to anyone working or interested in program management, regardless of their official job title or credentials. This usage differs from the typical professional usage, in which PgMP indicates the successful completion of the Program Management Professional (PgMP) certification offered by the Project Management Institute (PMI).