Want to become a better problem solver? Look to grand stories.

How fictional stories can serve as unlikely mentors for navigating program management's toughest challenges.

“No one at this point in history knows how to live. So, we read biographies and memoirs hoping to get clues.”

- Sheila Heti's Alphabetical Diaries

I heard this quote on “The Daily” podcast, as book critic Dwight Gardner shared his favorite lines from books over 2024. This statement resonated as I pondered my own growing fascination with biographies. I recently finished Katherine Graham’s beautiful tome “Personal History: A Memoir” and found that reading about the intricate details of a notable person’s outsized life still provided useful insights on my far daintier troubles.

PgMP Foundations: This article covers the concepts of simple versus complex problems in program management.That same idea can be applied to program management professionals (PgMPs) looking to expand their ingenuity. There’s tremendous value in reading/listening/watching true-life stories, but what about fiction? When a story is about a 19th-century pirate or an apocalyptic space society, what applies to designing and managing programs?

My best advice is to read/listen/watch for the problems.

Problem formation, escalation, and resolution…all parts of a problem are relevant. In particular, you want to read, digest, and internalize the shape of the mighty and deeply complex conflict.

Those simple problems…

As program management professionals (PgMPs), we are inherently problem solvers. Throughout much of my career, I viewed problem-solving as the skill enacted when something goes wrong in a plan, often at the project level. For example, a miscommunication about who is writing a grant report due in 48 hours (yup, that happened).

In shape, they may be 3-alarm fires to the welfare of projects, but these are straightforward problems. You know the actors, the cause is identifiable, and the fix is a hefty combination of reasonable analysis, solid interpersonal skills, and gritty hard work. These are the problems that you can package into the handy STAR format for future job interviews. And please do!

Good project management training helps us resolve these problems quickly or, ideally, prevent them in the first place. The issues that you want to train your brain to handle are far more complex. And that’s where stories—both non-fiction and fiction—can help us.

What is a mighty and deeply complex problem for a program?

For programs, the threats that jeopardize the longevity of our work are located where the program meets the business. Have you ever experienced your program unsnapping from your company? In my experience, the typical causes of a program’s downfall are less to do with internal functions and more often linked to external triggers such as budget deficits, strategic redirection, or leadership infighting. While these problems can be straightforward, such as job cuts in the Great Recession (2007 – 2009), often the factors combine in more obtuse ways.

I’ve encountered these complex problems several times in my career and experienced the resulting program decline first-hand. In all cases, it was a painful, frustrating, and strangely lonely phase of the job. Most disconcerting, I was successfully completing the program’s agreed-upon work, yet met with a convoluted waning of leadership’s support. The program then suffered a “death by a thousand cuts” as lousy news got passed in hallway conversations, resources reassigned, and champions left the company. Often, it was not immediately clear who was making the decisions about the program, nor who to trust when I asked questions. I was left piecing together a myriad of facts, sometimes over years, to reach a satisfying conclusion of the causes behind a program’s cancellation. My autopsy ultimately pointed to no single root cause, but numerous factors, each of which I’ve learned from to improve my ability to lead programs to success.

While I can’t make the realities of a program’s fall from grace disappear, one doesn’t want to, nor should rely solely on life experience to get a better handle on these situations. Further, while technical manuals about program management are great for foundational skill building, these are problems that don’t fall neatly into a framework either. In hindsight, I believe strategies exist that can help program management professionals prepare for and navigate through these deeply complex issues. Still, it takes a monstrously sophisticated level of business acumen, communication skills, and stress management to succeed. Preparing to weather these storms takes training. That’s where reading, watching, and listening to non-fiction and fiction stories can help us to better understand PROBLEMS.

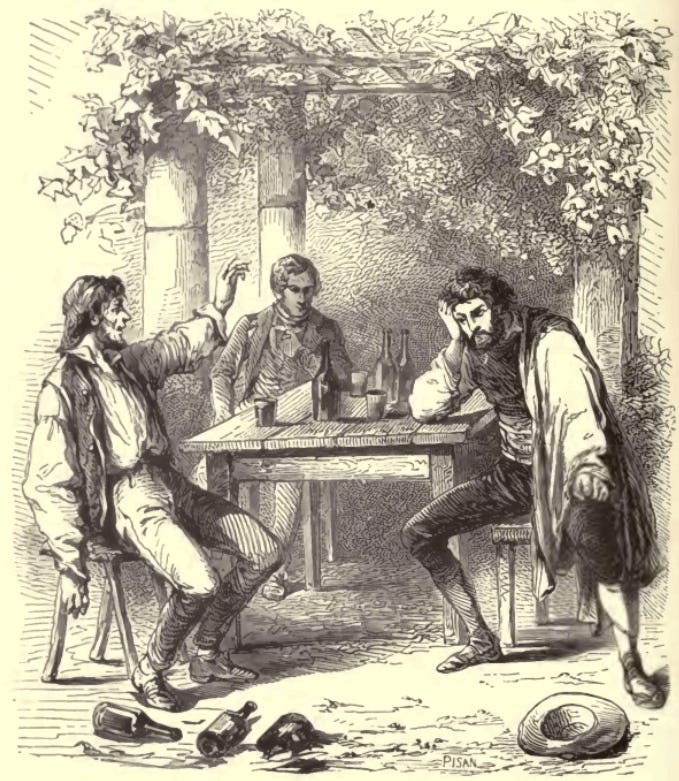

For example, “The Count of Monte Cristo” – an adventurous tale of a great complex problem

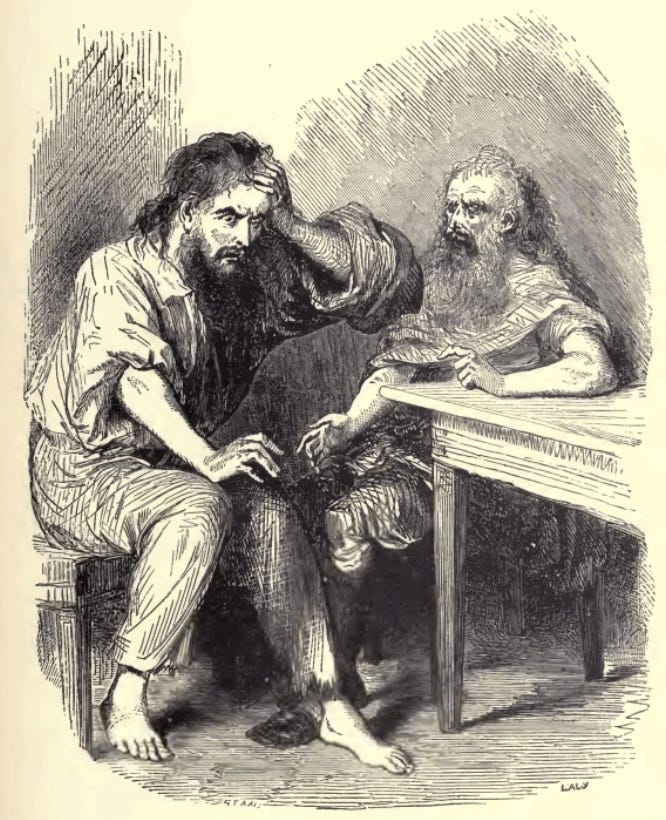

I’m currently reading “The Count of Monte Cristo,” written by Alexandre Dumas, published between 1844 and 1846. It is a revenge tale of Edmond Dantès, a man wrongfully imprisoned during the Napoleonic era. Upon escaping jail, he comes into a great fortune, which he uses to enact long, snaking revenge plots against those who falsely condemned him to imprisonment without trial. Looking back from the 21st century, I have little in common with the lives depicted in this story, but I still relate to and learn from Dantès’ circumstances. In particular, this novel begins with an incredibly convoluted problem: the setup behind the false accusations that led to Dantès’ imprisonment.

My first introduction to this story was the 2002 movie, where I only recalled that the betrayer was a jealous best friend. When reading the original text 20+ years later, I was surprised to find that Dantès’ betrayal is a much thicker interweaving plot of three primary villains and one toxically neutral observer. None of the betrayers were close friends to Dantès; all had different personal reasons for their actions, and each only formed a singular piece in the chain of events that led to Dantès’ imprisonment. Further, the actions were uncoordinated enough that each person could reasonably deny their culpability in condemning an innocent man to prison and likely death. All these interpersonal issues were then neatly woven into actual historical events of Napoleon Bonaparte’s re-emergence from Elba and the resulting Hundred Days War.

It’s a brilliant, fantastical, fully scaled-up plot. I nonetheless related to the story as it reminded me of the complexities I’ve experienced when a program fails. Namely, there are many actors with a soupy mixture of motives from valid business rationale to disconcerting biases. I found personal reassurance in that, in our modern day where simplicity is often preached, an author from two centuries back also saw how small actions can snowball into seemingly illogical outcomes. Further, how much the person most impacted can struggle to gain a foothold of understanding on “the why” behind their circumstances.

To that last point, Dantès spends years in solitary confinement, consumed by an inability to understand the cause of his imprisonment. Only when fellow inmate Abbé Faria tunnels into his cell with deus ex machina insight does Dantès come to understand the people and motives behind his demise. Through such absurd conditions, the author Dumas depicts other truths that are also applicable in business: how hard it can be to understand one’s situation and the value gained from an outside perspective.

Share your recommendations!

While I cannot advise we look to Dantès as the exemplar for how to solve a complex problem (i.e., please don’t spend decades enacting revenge), the beginning of his story gives insights nonetheless about problem complexity. Sometimes things go badly, and there is no one simple cause. Instead, there’s a universe of reasons that are worthy of understanding. As program management professionals, understanding problems is how we get better at our jobs and reach the goal of developing programs that can really help people.

What stories can you recommend to learn more about complex problems? Does anyone have a great read/listen/watch for learning how to resolve complex problems, or even prevent one from entirely unfolding?

References

Dumas, A. (1888). The Count of Monte Cristo. George Routledge and Sons. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1184/1184-h/1184-h.htm